Alternate methods of dispute resolution are amicable methods of resolving disputes without the intervention of courts. It decreases the burden of the courts and encourages settlement proceedings among the parties. Generally, Alternate Dispute Resolution (ADR) uses one or more neutral third parties who help the parties to communicate, discuss the differences and resolve the dispute. ADRs are a set of methods that enable individuals and group to maintain cooperation, and social order and provides an opportunity to reduce hostility.

Mediation is one such consensual party-centric process of dispute resolution where the two disputing parties come together to settle the dispute amicably with the aid of an impartial adjudicator, known as the ‘mediator’. Overall the other method of dispute resolution, mediation is preferred by the parties as it allows them to choose a mediator of their choice which can ensure a win-win situation for both parties as the process is primarily based on negotiation and understanding between the parties. Traditionally, one key element of mediation is that since the process is voluntary, the parties to the dispute are not obligated to agree to the settlement reached by the mediator. As such, the parties seeking mediation would be bound by its results only if they agree to it. In the present time, more and more reliance is being placed on these methods of dispute resolution to decrease the number of court cases.

With this legislative intent, Section 12-A of the Commercial Courts Act, 2015 (hereinafter referred to as the Act) was inserted by an amendment in the year 2018. The aim and object of Section 12-A are to ensure that before a commercial dispute is filed before the court, an alternative means of dispute resolution is adopted so that only genuine cases which need the court’s urgent attention, are adjudicated by the court.

Section 12-A reads as under:

12-A. Pre-institution mediation and settlement. — (1) A suit, which does not contemplate any urgent interim relief under this Act, shall not be instituted unless the plaintiff exhausts the remedy of pre-institution mediation in accordance with such manner and procedure as may be prescribed by rules made by the Central Government.

(2) The Central Government may, by notification, authorise the authorities constituted under the Legal Services Authorities Act, 19879, for the purposes of pre-institution mediation.

(3) Notwithstanding anything contained in the Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987 (39 of 1987), the Authority authorised by the Central Government under sub-section (2) shall complete the process of mediation within a period of three months from the date of application made by the plaintiff under sub-section (1):

Provided that the period of mediation may be extended for a further period of two months with the consent of the parties:

Provided further that, the period during which the parties remained occupied with the pre-institution mediation, such period shall not be computed for the purpose of limitation under the Limitation Act, 1963 (36 of 1963).

(4) If the parties to the commercial dispute arrive at a settlement, the same shall be reduced into writing and shall be signed by the parties to the dispute and the mediator.

(5) The settlement arrived at under this section shall have the same status and effect as if it is an arbitral award on agreed terms under sub-section (4) of section 30 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 (26 of 1996).]

Section 12-A, by introducing the word “shall”, made the pre-suit institution mediation proceeding mandatory only with reference to plaintiffs who do not contemplate urgent interim relief. As per the Act, mediation under this section is a time-bound process to be conducted by the respective State Legal Services Authorities (Authority), constituted under the Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987. The period for conducting such mediation has also been expressly excluded by the Legislature under the Limitation Act, 1963.

The only exception contemplated under Section 12-A is for a party seeking urgent interim relief. The Act, however, does not define what would be considered an “urgent interim relief” and the same is left to the discretion of the Court. Recently, it has been seen that Section 12-A of the Act is not mandatory in cases involving intellectual property rights where urgent interim relief is sought.

Process of Pre-litigation Mediation as per the Commercial Courts (Pre-Institution Mediation and Settlement) Rules, 2018

Initiation of mediation process —

- A party to a commercial dispute needs to make an application to the Authority as per Form-1 in Schedule-I, either online at (https://nalsa.gov.in/lsams/nologin/mediation.action?requestLocale=en) /by post/by hand, for initiating mediation process along with INR 1000/- as fees payable to the Authority by demand draft/ online;

- The Authority shall, having regard to territorial and pecuniary jurisdiction and nature of the commercial dispute, issue notice, as per Form-2 in Schedule-I through registered/speed post and send e-mail to the other party to appear and give consent for participating in mediation proceedings on a date which is not beyond ten days from issue of notice. The following three situations can arise:

- No response from the opposite party- In this case, the Authority shall issue final notice;

- The opposite party refuses to participate or does not acknowledge the final notice of the Authority stated above – If this is the case, the Authority shall treat the process to be a non-starter and make a report as per Form 3 in Schedule-I and endorse it to both the parties;

- The opposite party, after receiving the notice, seeks further time for appearance– In this event, the Authority may fix an alternate date for appearance not later than 10 days from the date of receipt of such request. If the opposite party fails to appear even on such an extended date, the process is treated as a non-starter under Form 3.

- Where both parties appear and give consent to participate in the mediation process, the Authority shall assign the commercial dispute to a Mediator and fix a date for an appearance before the said Mediator.

- The Authority shall ensure that the mediation process is completed within 3 months from the date of receipt of an application for pre-institution mediation unless the period is extended for 2 months with the consent of both parties.

Mediation Fee:

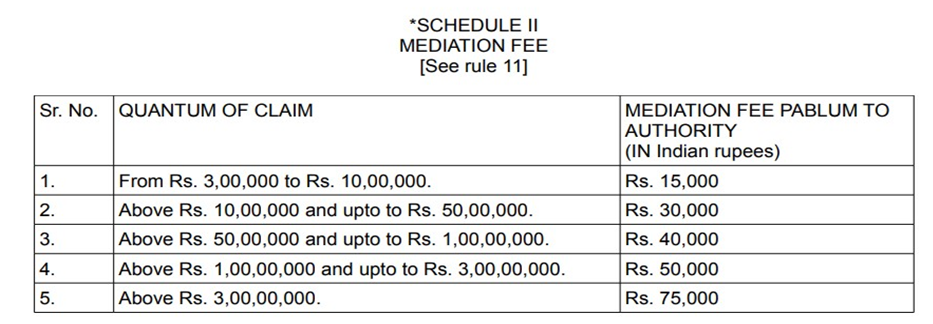

Before the commencement of the mediation, the parties to the commercial dispute shall pay to the Authority a one-time mediation fee, to be shared equally between the parties, as per the quantum of the claim as specified in Schedule II of the Act.

Implications of introduction of Pre-litigation Mediation requirement

After Section 12-A was introduced, a difference of opinion arose among the courts with regard to the nature of the section being mandatory or merely a directory. The courts had to consider as to whether plaints instituted without recourse to mandatory pre-institution mediation ought to be rejected upon an application being filed under Order 7 Rule 11 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (CPC).

In the case of Patil Automation Private Limited and Others v. Rakheja Engineers Private Limited, 2022 (SCC Online SC 1028), the Supreme Court put this controversy to rest. The Court has held that the requirement of exhausting pre-institution mediation under Section 12-A of the Act is mandatory and that any suit instituted “violating the mandate of Section 12-A must be visited with rejection of the plaint under Order 7 Rule 11”.

However, the Delhi High Court in its recent judgments has observed that in intellectual property cases, where the matter affects not only the disputants but also the consumers and public interest, then the plaintiff’s application seeking exemption from instituting pre-litigation mediation proceedings is in accordance with section 12-A of the Act can be allowed. Thus, it has been seen that Section 12-A of the Act is not mandatory in cases involving intellectual property rights where urgent interim relief is sought.

Drawbacks of mandatorily enforcing Section 12-A

While the intent behind the introduction of pre-institution mediation was to increase settlement proceedings and reduce unnecessary litigation burden on the courts, there are some inadequacies. Mediation is preferred over any other mode of dispute resolution as it is a consent-based process in which parties voluntarily opt to resolve their disputes under the guidance of a mediator. However, Section 12-A of the Act has forced the parties not seeking urgent interim relief, to necessarily go through the mediation process. Moreover, it is only mandatory for the party instituting the suit to institute the mediation by approaching the Authority while the defendant may altogether abstain from responding to the mediation request. Thus, it is now treated as a mere obligation that the party treats as merely a technical step to overcoming in order to institute the suit and sometimes a mere dilatory tactic used by defendants.

Further, the choice of parties to pick a mediator has been taken away and the process is conducted by a mediator allotted by the Authority constituted under the Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987. Parties ideally would pick a mediator suited to their needs and requirements who has knowledge of the field in which the parties operate. The parties would not be able to trust the mediator and may not have faith in the mediator’s ability to help them arrive at a mutually beneficial solution. Thus, the whole essence of mediation is being hampered.

Lastly, a party can avoid mandatory pre-institution mediation by seeking urgent interim reliefs. Since no parameter has been set out for considering “urgent interim reliefs”, it is left to the discretion of the courts to be decided on a case-to-case basis and is thus fairly subjective. For instance, the Delhi High Court in Upgrad Education (P) Ltd. v. Intellipaat Software Solutions (P) Ltd (2022 SCC OnLine Del 644) via judgment dated February 28, 2022, has held that in suits filed before the intellectual property division, where an application for interim injunction is filed and urgent interim relief is sought, the leave to directly institute the suit would be presumed in view of the language of Section 12-A and a separate application would not be required. The Court has further clarified that even if urgent interim relief is sought by the plaintiff, the Court is of the opinion that the parties ought to be relegated to mediation, an order referring the matter to mediation can always be passed.

As such, the status quo is such that a plaintiff, despite having exhausted all means of resolving a dispute amicably, either mandatorily institutes the mediation process before filing the suit to avoid objections from the defendant on technical grounds or directly files the suit claiming urgent interim relief – admittance of which would depend on the Court’s discretion. The peril here is that what may be urgent or extremely important to one may not be for another. Also, in cases involving intellectual property rights, any such urgency of relief will be adjudged against the larger public/ consumer interest.

This article has been authored by Sampada Kapoor, Selvam & Selvam. Sampada graduated from law school at Panjab University and pursued her Post Graduate Diploma in Intellectual Property from National Law School. Being a first-generation lawyer, her quest to expand her expertise in the area of Intellectual Property Rights lead her to secure a Master’s in Intellectual Property Rights from Amity University.

Editorial Staff

Editorial Staff at Selvam and Selvam is a team of Lawyers, Interns and Staff with expertise in Intellectual Property Rights led by Raja Selvam.

Understanding well-known trademarks application in India

The article aims to shed light on the nuances of well-known trademarks. It is divided into three parts: Part I discusses the origin and statutory…

IPAB makes the Indian Patent Office see the importance of doing things right the first time

In a spate of orders recently (see here, here and here), the Intellectual Property Appellate Board (IPAB) has asked the Indian Patent Office (IPO) to…

International Non-Proprietary Names as Trademarks in India – INN or OUT?

International Non-Proprietary Names (INN) are globally recognized names for pharmaceutical substances or active pharmaceutical ingredients and are…