The primary purpose of a trademark is that it serves to distinguish the goods or services of one person from those of another. If a mark is not distinctive, it could lead to confusion in the minds of consumers and deceive them as to the origin of the product or service it represents. To prevent such confusion and deception, Section 9(1)(a) of the Trade Marks Act prohibits the registration of any mark which lacks distinctiveness. It is thus important to examine how a person wishing to have a mark registered can ensure that it is distinctive.

Classification of Trademarks on the basis of distinctiveness

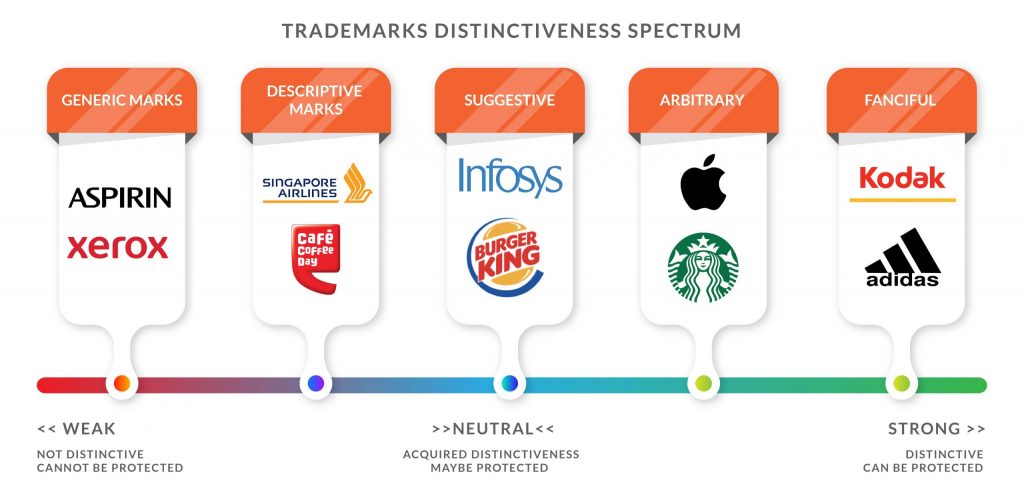

In Abercombie & Fitch Co. v. Huntington World Inc., decided in 1976, the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit established a spectrum of trademark distinctiveness under which marks can be broadly classified into five categories. Each of these categories has different degrees of distinctiveness. On the basis of the degree of distinctiveness of a mark, it can be perceived whether a mark is capable of being registered or not. The following are the five categories:

a) Fanciful Marks

These are words, symbol or devices which have been expressly invented/coined for the purpose of serving as a trademark. They have no relationship with the good or service being sold. This type of mark is considered to be the strongest for registration due to its unique nature which leaves no room for ambiguity as to the origin of the product or service it represents. E.g: Konica and Adidas.

b) Arbitrary Marks

These marks are words which are used commonly but do not have any relationship with the products or services they represent. Arbitrary marks are also strong marks which are capable of being registered. E.g., Apple, Uber and Kindle.

c) Suggestive Marks

This type of mark suggests that the good or service it represents has a particular quality without describing it completely. A leap of imagination on the part of the general public is required to understand the product or service the mark is used for. While these marks are considered registerable, they are not considered to be as strong as fanciful or arbitrary marks as there is a danger that they might not be distinctive enough. E.g., Galaxy Tab, iPhone and redBus.

d) Descriptive Marks

These marks describe the purpose, nature or an attribute of the product or service and are not considered to be eligible for registration. However, in exceptional circumstances, a descriptive mark could be registerable if it has acquired distinctiveness—through long-term usage in the eyes of consumers. E.g., if the mark “Car Wash” were used to represent a car washing business, it would not be registerable.

e) Generic Marks

These marks are the actual names of the products or services they represent. They are not eligible for registration under any circumstance. E.g., the mark “Phone” for a phone would be ineligible for registration.

In order to ensure that a mark is registerable, a person wishing to register a mark would have the best chances of success if the mark is either fanciful or arbitrary. These types of marks also have the added advantage of enabling products and services to stand out in competitive markets and create strong impressions in the minds of consumers. Thus, categorising trademarks through the trademark distinctiveness spectrum is a useful exercise to determine which end of the spectrum the trademark falls.

Written by Krithajnya Raghunathan

Editorial Staff

Editorial Staff at Selvam and Selvam is a team of Lawyers, Interns and Staff with expertise in Intellectual Property Rights led by Raja Selvam.

Agreements on trade secrets and confidential information – Enforceable in India?

It is not the answer that enlightens, but the question.This is rather apt for the India IP scenario where many individuals and companies have been…

Delhi HC allows amendments to trademark applications

We had recently written about an order that was passed by the Controller General of Patent, designs and Trademarks restricting the amendments that…

Trademark Application Status “Exam Report Issued” – Explained

Many a time, the online status of a mark shows ‘ exam report issued ,’ perceiving which, one might assume that it implies ‘issuance of examination…